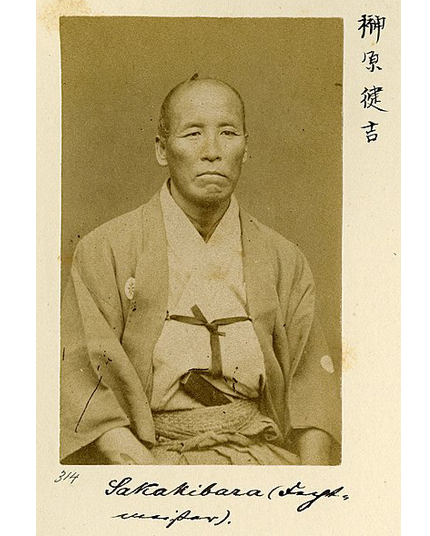

The origins of kenbu as a performing art go back to 1873, when the swordsman Sakakibara Kenkichi began to show kenjutsu (swordplay) performances, called Gekiken fencing show, as a measure against the decline of kenjutsu dojo (training halls). In the manner of sumo wrestling, kenjutsu matches used to be staged in front of the general public, with sword dance performances inserted for entertainment between the matches. This is how kenbu became widely known at one bound, and Gekiken fencing show and kenbu rapidly increased and gained popularity all across Japan. One of the kenjutsu masters at the time was Hibino Raifu, who founded the Shinto-ryu (Shinto school) in Tokyo, and thereby established the style of present-day kenbu combining poetry recitation and dance with swords and fans. Next to the Shinto-ryu, there exist a number of other schools as well that helped originate kenbu, and it is via branches of such schools that kenbu established itself as something to be practiced in okeikogoto (“individual enrichment courses”).

The leaders of the late Tokugawa period were the first to perform dances with their swords.

paragraph 1

As in any other field, the question “when it all began” is difficult to answer precisely also in the case of kenbu. When the sword itself was brought to Japan from the Asian continent, the tradition of using it in dance performances may have been imported at the same time. In terms of records of “dancing with a sword,” such practices have been mentioned as early as in the “Taiheiki” (a war chronicle of the 14th century). But there is no historical connection between those practices and today’s kenbu, and it seems that there is a gap regarding the respective origins.

paragraph 2

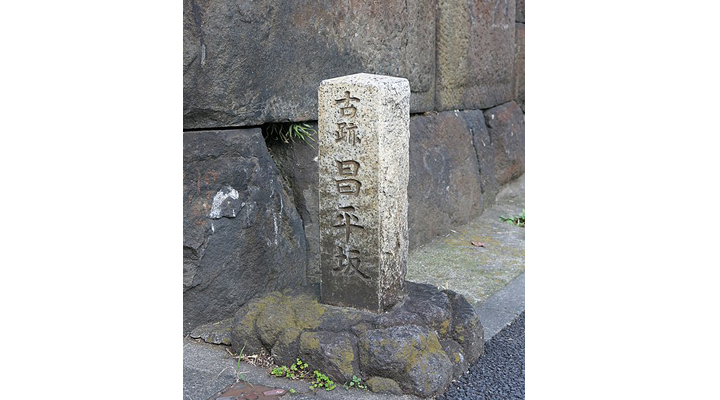

About the direct origins of kenbu, there exists a popular theory that drunken students of the Shoheizaka school were the first to draw their swords while chanting classical Chinese poems, and this may be the easiest explanation of how the tradition of sword dance started. Some kenbu practitioners, however, reject this theory, based on the martial artistic idea that the sword is a tool that isn’t all that easy to handle. Anyway, personally I consider the aforementioned episode to be rather essential when it comes to defining the origins of kenbu.